In the bewildering galaxy of gods of the Hindu pantheon, Lord Shiva stands out as one of the oldest and best loved. He is as old as the Indian culture, perhaps even older.

At the time of the cosmic dawn, before the creation of man, he appeared as the divine archer, pointing with his arrow to the unrevealed Absolute. The world is his hunting ground. The universe resounds with his presence. He is both sound and echo. He is intangible vibration as well as infinitesimal substance. He is the rustling of the withered leaves and the glossy green of the newborn grass. He is the ferryman who ferries us from life to death, but he is also the liberator from death to immortality. He has innumerable faces and eleven forms as described in the Vedas. The sky and the seasons vibrate with his intensity and power. He grips, supports, releases, and liberates. He is both the disease and the destroyer of the disease. He is food, the giver of food, and the process of eating. His divine majesty and power are depicted through symbolic, yet highly realistic descriptions of an awe-inspiring figure, far, distant, and cold in his remote Himalayan fastness as well as close, kind, and loving, a living, throbbing symbol of the Divine.

He was worshipped as the divine shaman by wild tribes that roamed across the subcontinent before the dawn of history. They contacted him by the use of certain psychoactive compounds and various esoteric rituals. Later we see him on the terra-cotta seals of the Indus civilization. There he is shown as Pasupati, Lord of beasts, surrounded by the wild creatures of the jungle. He is also shown as the yogi sitting in various meditative postures. The rishis of the Vedas looked up at the Himalayas and saw in them his hair; they found his breath in the air, and all creation and destruction in his dance—the Thandava Nritta. The Rig Veda, the oldest religious text known to humankind, refers to him as Rudra, the wild one, who dwelt in fearful places and shot arrows of disease. Sacrifices were constantly offered to appease him.

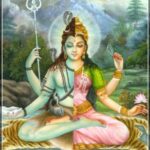

At that time religion was dominated by female deities, so the cult of Shiva soon fused with that of the great Mother Goddess Shakti, who later came to be known as Durga, Uma, Parvati, and so on. Male and female are but complementary halves of the whole truth, and some images portray Shiva as Ardhanareeswara, a form half male and half female.

In the Tantric cosmology, the whole universe is perceived as being created, penetrated and sustained by two fundamental forces, which are permanently in a perfect, indestructible union. These forces or universal aspects are called Śiva and Śakti.

The tradition has associated to these principles a form, respectively that of a masculine deity and that of a feminine one. Accordingly, Lord Śiva represents the constitutive elements of the universe, while Śakti is the dynamic potency, which makes these elements come to life and act.

From a metaphysical point of view, the divine couple Śiva-Śakti corresponds to two essential aspects of the One: the masculine principle, which represents the abiding aspect of God, and the feminine principle, which represents Its Energy, the Force which acts in the manifested world and life itself.

Śakti here stands for the immanent aspect of the Divine, that is the act of active participation in the act of creation. This Tantric view of the Feminine in creation contributed to the orientation of the human being towards the active principles of the universe, rather than towards those of pure transcendence.

Therefore, Śiva defines the traits specific to pure transcendence and is normally associated, from this point of view, to a manifestation of Śakti who is somewhat stronger (such as Kali and Durga), personification of Her own untamed and limitless manifestation.

Owing to the fact that in a way, Śakti is more accessible to the human understanding (because this regards aspects of life that are closely related to the human condition inside the creation), the cult of the Goddess (DEVI) has spread more forcibly.

Śaktism’s focus on the Divine Feminine does not imply a rejection of Masculine or Neuter divinity. However, both are deemed to be inactive in the absence of Śakti. As set out in the first line of Adi Shankara’s renowned Shakta hymn, Saundaryalahari (c. 800 CE): “If Śiva is united with Śakti, he is able to create. If he is not, he is incapable even of stirring.” This is the fundamental tenet of Śaktism, as emphasized in the widely known image of the goddess Kali striding atop the seemingly lifeless body of Śiva.

Broadly speaking, Śakti is considered to be the cosmos itself – she is the embodiment of energy and dynamism, and the motivating force behind all action and existence in the material universe. Śiva is her transcendent masculine aspect, providing the divine ground of all being.

“There is no Śiva without Śakti, or Śakti without Śiva. The two […] in themselves are One”.

There are many aspects, forms and names of Śakti who is the mother of all. In creation she distinguishes herself, or through the will of Śiva, into three basic aspects:

para-Śakti (transcendental energy),

apara-Śakti (immanent energy) and

para-apara-Śakti ( an intermediary energy).

In the texts of Shaivism we also find a reference to five supernatural powers of Śakti, awakened in himself by Śiva. Their permutation, combination, concealment and manifestation is believed to be responsible for the multiplicity, plurality, diversity and duality of the beings and objects and their forms and shapes in the manifested worlds. The five aspects of Śakti manifested by Śiva are:

cit-Śakti or the power of consciousness,

ānanda-Śakti or the power of bliss consciousness,

iccha-Śakti, the power of desire or will,

krīya-Śakti the power of action and

jñana-Śakti or the power of knowledge

Śiva unleashes these five powers in the beginning of creation and withdraws them back into himself at the time of dissolution. In between he employs these energies for the purposes of creation (srishti), preservation (sthithi), samhara (destruction or modification), concealment (tirobhava) and revelation (anugraha).

There is no Śiva without Śakti and yoga is a realization of the unity of all things.

That is not to say that everything in tantrik texts is figurative; many describe practices which are said to bring about this realization.

Source: Vanamali and Templepurohit articles